A moose strikes a commanding pose in a clearing at the base of a snowcapped mountain, his splendid rack of antlers a testament to the number of years he’s survived the wild. It’s a sight few of us will ever see, but one that’s very familiar to Jay “Bird” Jones who grew up in Colorado and spent eight years working for the Forest Service in northern Idaho.

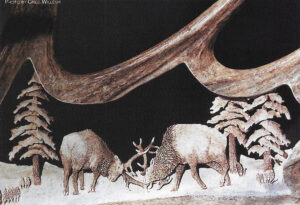

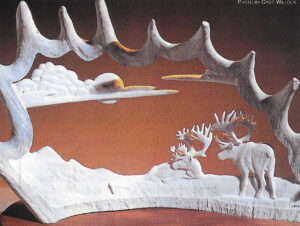

It’s also a scene you’ll find in his wildlife art. When Jay was young, his dad nicknamed him “Jay Bird,” and he is one of only a few artists who carve moose antlers.

He began carving wood objects in the mid ‘70s. By 1980, he was working for the Forest Service and was soon carving bolo ties and buckles out of antlers which were easy to find in the timber. He then moved up to working with the larger moose antlers, and those experiments resulted in the three-dimensional art forms found in his works today.

He began carving wood objects in the mid ‘70s. By 1980, he was working for the Forest Service and was soon carving bolo ties and buckles out of antlers which were easy to find in the timber. He then moved up to working with the larger moose antlers, and those experiments resulted in the three-dimensional art forms found in his works today.

Moose shed their antlers annually. In fact, they’re shed in the middle of winter, long before elk or deer lose theirs. Each year they grow back a little bigger than the year before, and each is different. Because of this quality, Jay says it takes time and planning to produce a special scene that utilizes the individual shape of each antler.

“All of the moose antlers are so unique,” Jay says. “You get a lot of ideas just looking at the antlers.”

He’s not alone in the process, however. His wife, Debbie, shares his love for nature. They were both working for the Forest Service when they met. His carving talents complement her drawing and painting abilities. The team produces an opportunity to recreate the splendor found in the country around them. Debbie draws the scenes; Jay carves them.

He’s not alone in the process, however. His wife, Debbie, shares his love for nature. They were both working for the Forest Service when they met. His carving talents complement her drawing and painting abilities. The team produces an opportunity to recreate the splendor found in the country around them. Debbie draws the scenes; Jay carves them.

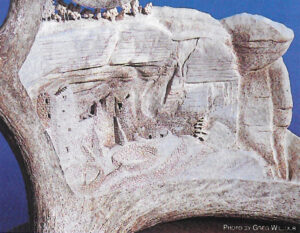

“Both of us look at the antler, and then we both talk about what we want to do with it,” Jay explains. “Would it look best cut off and on a wooden base? Or the whole antler in itself? Or a wall hanging?”

Debbie continues the explanation by saying that Jay cleans up the face of the antler while she starts with the outline of the antler on tracing paper.

“I work on the tracing paper and get it drawn on there,” she says. “Then I draw it on top of the antler to make sure it’s all lined up. And then I use carbon paper on the back of the drawing to get it on the antler.”

That leaves Jay to cut out the silhouette and start carving what is left. He says the antler is of a harder quality than most kinds of wood. However, there are times he’ll get to the center of the palm of the antler and it will be too porous to carve on. Diet can sometimes affect the quality.

That leaves Jay to cut out the silhouette and start carving what is left. He says the antler is of a harder quality than most kinds of wood. However, there are times he’ll get to the center of the palm of the antler and it will be too porous to carve on. Diet can sometimes affect the quality.

According to Jay, “It seems like whatever they’re eating, the minerals and stuff that they get, contributes a lot to the density of the antler and the size…”

Author and avid outdoorsman David Petersen says the size and condition of the racks also depend upon the age and bodily condition of the animal. In his book, Racks, he explains that a breeding-age male will produce “impressive antlers that advertise his prowess; when he grows weaker (through injury, disease, starvation or old age) he produces smaller antlers that indicate he is out of the competition and thus will not provoke antagonism from a superior rival.”

After the carving is finished, Jay takes the piece back to Debbie who then does the staining—if they’ve decided it would enhance the scene. This is what sets their work apart from the others. Most antler artists leave their etchings in the raw, white state found after carving.

After the carving is finished, Jay takes the piece back to Debbie who then does the staining—if they’ve decided it would enhance the scene. This is what sets their work apart from the others. Most antler artists leave their etchings in the raw, white state found after carving.

Jay and Debbie used to make an outing once a year to find moose antlers. They would head back to his old stomping grounds, the Fenn Ranger Station in northern Idaho. It was easy to get him to reminisce.

“We’d set up timber sales, he says with a faraway look in his eyes, the corners of his mouth turning into a smile. “One summer, in three months, we found 70-some moose antlers in one little area…and I’d go back every year and find some in the same area. Mostly we’re buying them off of antler dealers now because we can’t spend that much time looking anymore.”

Antler hunting seems to be a form of entertainment itself. As Jay puts it, “It’s like an Easter egg hunt. You get out there looking, and you see their sign all over, and it’s just more fun to find an antler than anything I’ve ever done, almost.”

He also has his share of stories about these excursions. Like the day he was chased…twice.

He laughs as he tells about trying to get the picture of a big cow moose, not realizing her calf was anywhere near.

“I thought for sure she was 20 feet away,” Jay says, shaking his head. “All of a sudden, next thing I know, she’s right on top of me, almost. I got around this big tree, and she chased me halfway around the tree and then took off. Her hair was standing up on her neck.” Was his? He just laughs.

His second encounter that day was with a bear.

“It was kind of waddling down the road toward me, and I didn’t think much of it,” Jay says, thinking back. “It was a couple hundred feet away. All of a sudden he darts up the hill of the bank and up comes Mama from the lower bank. And she comes running straight at me with her mouth and teeth bared. She was a hundred feet away, and I’m screaming at the top of my lungs. She just darted off and started down the hill again. It was a full day!”

One of Jay’s favorite areas for picking up moose antlers are the Pacific Yew Woods in the northern states. However, with the discovery of Taxol, the cancer drug derived from the bark of the yew, many of those areas are being cut down, forcing the moose to move. But, Jay says, they can survive in a lot of different habitats.

One of Jay’s favorite areas for picking up moose antlers are the Pacific Yew Woods in the northern states. However, with the discovery of Taxol, the cancer drug derived from the bark of the yew, many of those areas are being cut down, forcing the moose to move. But, Jay says, they can survive in a lot of different habitats.

The price for moose antlers seems to be about the same as deer…about $6 a pound. Jay says an unusual piece like a big rack or a matched set will sell for more. And a full rack could be 25 pounds or more. In fact, according to Joe Van Warmer, author of The World of the Moose, the antlers of a mature Alaskan bull moose weight from 60 to 85 pounds.

If an antler is found in the spring, Jay says it’s usually still in good condition. Once it’s been carved or mounted, it will last a lifetime. The key is keeping it out of the sun.

Antlers left in the timber into the summer months can dry out, bleach and crack. Plus porcupine, mice and other forest creatures feed on them for the calcium. So, the Jones’ do their part for the environment by taking their antler scraps with them and throwing them back into the woods.

Antlers left in the timber into the summer months can dry out, bleach and crack. Plus porcupine, mice and other forest creatures feed on them for the calcium. So, the Jones’ do their part for the environment by taking their antler scraps with them and throwing them back into the woods.

“We’re taking stuff out of the woods that mice and squirrels would be eating,” Jay says. “So we try to put a little bit back every time. We’re not using the stuff anyway, it’s scraps.”

It’s also important to note that several wildlife biologists were asked by David Petersen about rodents depending on antlers as an important source for nutrition. He says, again in his book Racks, that they replied almost as one that “while castoffs make nice bonuses for the rodents that find and gnaw on them, antlers are not an essential part of the food chain.”

He also says the “cast antlers are so relatively rare and widely scattered that the overwhelming majority of rodents live their entire lives without encountering a single one.” So, unless the activity is prohibited by law in a park or preserve, there’s no reason to feel guilty about picking up cast antlers.

According to Jay, completing a piece can take anywhere from two to ten days depending on the detail. However, as Debbie points out, it ends up being almost a 24-hour-a-day job when you’re constantly thinking about ideas for antlers. She tries to sketch it out before she loses the image, no matter what the time of day.

According to Jay, completing a piece can take anywhere from two to ten days depending on the detail. However, as Debbie points out, it ends up being almost a 24-hour-a-day job when you’re constantly thinking about ideas for antlers. She tries to sketch it out before she loses the image, no matter what the time of day.

Each piece is original, or a one-of-a-kind, because it’s hard to find two antlers exactly alike. But, as Debbie says, “If somebody sees one and says they want one like that, we can say we’ll do it but it will be a little different because the antler shape is not identical.”

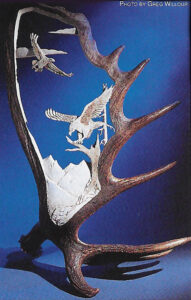

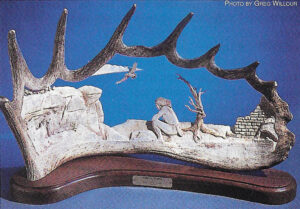

Their most unusual custom order was a matched set of moose antlers, mounted together with two eagle heads carved on the ends. Mountains were silhouetted in the background, and the eagles looked like they were flying toward each other, dogfight style. Jay says they connected a light to the back so the silhouette would show up well.

He also says they’re beginning to get into more functional pieces like table lamps with carvings in them and elk antler chairs. They’ve also done a number of chandeliers made out of mule deer antlers. Again, by combining the different shapes in various ways, the possibility of creating unique chandeliers is endless.

The fascination with antlers has been with us since the phenomena of antler growth and development first began. To be able to couple that interest with the work of someone like Jay “Bird” Jones only enhances an already beautiful object. It’s all the more evident that his finished product is the result of a deep love and respect for one more of God’s many wonders.

# # #

You can find out more about Jaybird’s work on his website, jaybirdantlercarving.com. He is also on facebook at Jaybird Jones and instagram at Jaybird.Jones.

You can find out more about Jaybird’s work on his website, jaybirdantlercarving.com. He is also on facebook at Jaybird Jones and instagram at Jaybird.Jones.